(States of Mizoram, Manipur, and Nagaland, India: November, 2000): On our return bus trip from Sielmat to Imphal, we bumped into some surprises. The military had expanded and greatly intensified its presence. Tomorrow the governor of the area will be speaking at a cultural event in Churachandpur. He will be traveling the same road we’ve traveled, and the speaking platform and performance stage were built not too far from the Christian hospital where we are working.

Apparently, the military had been alerted to the possibility of the local underground insurgents making a protest somewhere during the event. Soldiers of the Indian National Army lined the roads, manned machine-gun roadblocks, and could be seen at every intersection, along the edges of the rice fields, and in armor-plated minitanks. Truckloads of the regional Assam Rifles military forces could also be seen wearing full combat gear, with old M-16 rifles over their shoulders or AK-47 automatic rifles in their laps. They certainly were expecting something.

Our bus was stopped several times, and on a couple of occasions, armed soldiers boarded our bus with guns drawn to find out who we were. It’s comforting to know they’re in the area to keep things under control.

It was about an hour after dark by the time we unloaded from the bus at the Imphal hotel. Some of the group said they had heard gunshots during the night quite close to the hotel. But since the Assam Rifles headquarters is on the other side of a water moat not far from our hotel, any importance ascribed to the alleged gunfire was quickly dismissed.

Wednesday, November 1

Drew ate some mutton curry on rice last night, and by this morning he was regretting it and swearing to never look at mutton curry again as long as he lives. We decided it would be the better part of wisdom for him to just stay close to the bathroom for the day. The rest of us piled into the bus and headed to Sielmat to work. The military presence had been heightened even more overnight, but our group took all the pressure in stride and accomplished our respective agendas.

This evening we visited the Imphal Christian school and enjoyed dinner there. As we drove back to the hotel property, we saw military vehicles and armed soldiers stationed outside the hotel gates. Even other hotel guests were talking about the increased military presence.

Thursday, November 2

This morning Drew was feeling well enough to join the rest of the group. We decided to leave the hotel half an hour earlier just to give us sufficient time on the road. Before we pulled out of the hotel driveway, we had determined that we would travel a circuitous route to Sielmat and stay off the main road to save time and the inconvenience of stopping at military checkpoints. The alternate route took us along inferior roads that at times crossed over the tops of the rice-paddy dikes.

But everyone agreed there was no sense in traveling the main road, where the military presence was so strong. We didn’t want to experience any unnecessary delays.

One of the local church leaders with us had heard that a dissident group of university students had blocked and closed the main road and the entry to the airport, which we passed every day. The insurgent group was demanding some specific concessions from the government before they would call off the strike and road closure.

Our group agenda for today included participating in the dedication ceremonies of a newly built church at Lamka, which is situated quite close to the Sielmat hospital. Our alternate route turned out to be very rough and pocked with deep washout spots from the rainy season. I was riding at the front of the bus in the seat adjacent to the driver. We had just made a sweeping curve and started down a long hill. I watched the driver put his foot on the clutch to shift the transmission. The clutch pedal went to the floor, but instead of springing back up and engaging the transmission, the pedal just stayed on the floorboard. The driver kicked at the pedal several times with no result. The road leveled out, and the bus slowly came to a halt, stopping in the middle of a bad stretch of washed-out road.

The driver became a little more animated as he reached down and pulled the pedal off the floor by hand. Nothing happened. The transmission seemed to be shifting fine, but the clutch mechanism was broken and wouldn’t engage. We were stuck out in the middle of nowhere. Mobile phones were nonexistent, and towing companies were a distant figment of past recollections.

We all disembarked from our immobile dinosaur and laid hands on its tail long enough to push it out of the center of the road. After we had brainstormed several impractical possibilities, a man who had passed us earlier in a bus returned with a small, heave-green-colored army jeep that sported a blue plastic tarp over the back, suspended by split-bamboo sticks. He suggested that he could take a few of us at a time to some town about thirty-six kilometers away, where we could catch a local death-trap bus that would likely be able to take us on the back roads to Sielmat. We bought into his plan except for the part where our group would get split up, with some of us waiting and some of us traveling for several hours. That wouldn’t have been safe.

It seemed the only viable option was for all twelve of us to try to squeeze into the jeep with all our belongings. We ended up with five adults in the front two seats and seven squeezed into the back under the flapping blue tarp. The ride certainly became a close bonding situation as we joined hips Siamese style. About an hour and fifteen minutes later, the jeep delivered us to the dusty intersection of a small village. There, the driver of one of the famous, intimidating Tata buses waited impatiently for us to board his bus, which was already loaded with suitcases and other pieces of unnecessary stuff.

By the time we pulled into the town bus barn in Churachandpur, we had stretched the usual two -hour trip into a full six-hour ordeal. The real miracle was that we even made it to Sielmat at all. Because of our untimely delays, the church dedication was rolled back to later in the afternoon.

The dedication, once started, went off without a hitch, and everyone was so proud of the new brick sanctuary building. Visiting church choirs had come to share in the ceremony, and at the close of the regular service, we all filed out into the churchyard, where we were served sweet juice and gummy bread while the youth groups put on a cultural program of ancient dancing in their colorful tribal outfits. At one point, the dancers came over and pulled us white folks into the circle and had us do some kind of a chicken-mating dance with them.

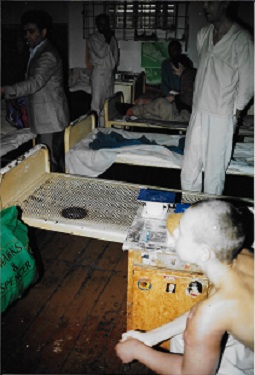

While we were engaged in the festivities, the rest of the world was in chaos. The military situation had taken a turn for the worse and had erupted into tragic violence. At about 3:30 p.m., some of the striking insurgents allegedly detonated a bomb in the ranks of the Assam Rifles military organization. The blast killed one soldier outright and wounded others. It was reported to us and later in the newspapers that when the Assam Rifles group realized that one of their men had been murdered, they retaliated with lightning speed by opening fire on civilians at a bus stop not far from the airport, killing ten on the spot and injuring some thirty others.

It didn’t take long for us to size up the situation and realize we were in a pickle. Now, all the roads back to Imphal were blocked. We couldn’t return to the capital city, but we couldn’t legally stay where we were. Either way we were in trouble. The military was moving with vengeance, and the strikers would try to take advantage of the high-profile incident and the momentum it ignited.

Next Week: Wrong Place at the Wrong Time