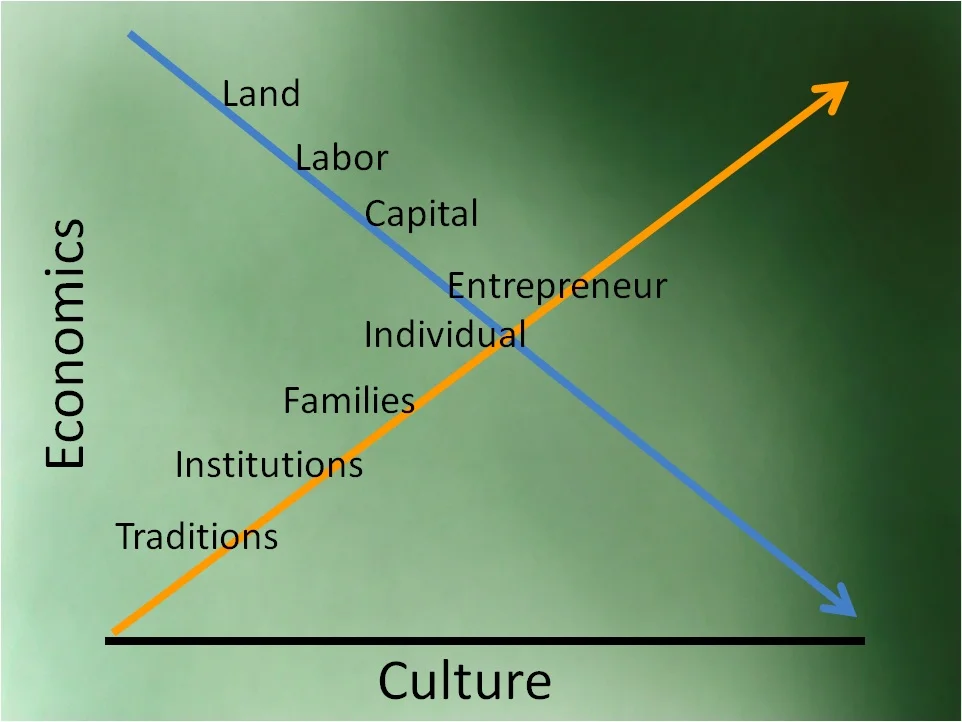

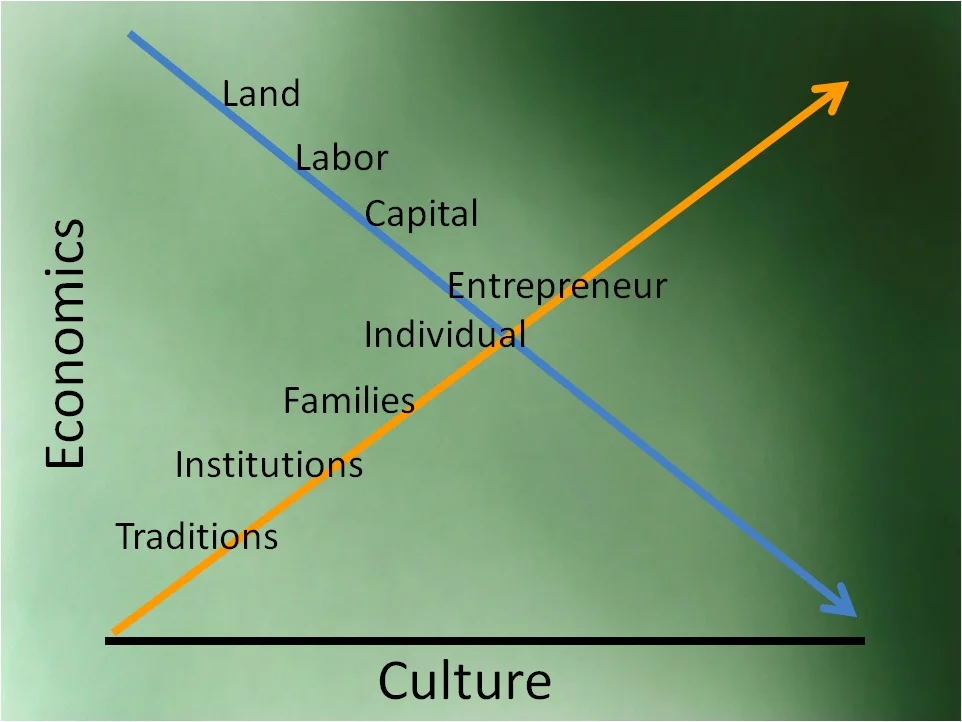

Every individual stands on the curbside of the intersection of culture and economics. That is where global transformation, as well as any other change, takes place. Culture will influence, and indeed has the power within it, to change economic philosophy and economic systems at that intersection. Conversely, economic systems and ideas have the power to change a given culture.

Just think of the potential capacity for change that is wrapped up in the individuals with their personal market baskets, gathered on the curbside of that intersection. Quite frankly, I find that potential dynamism quite fascinating. There is potential capacity to perform, to yield, or to withstand any and all components of culture or any and all components of economics as they try to intersect, collide, and pass through that intersection. The components that make it through to the other side of the intersection will determine history as it is recorded.

I am additionally intrigued by the variety of emotional, moral, and behavioral capacities that influence the components of economics and culture as they pass through the intersection. The traffic flowing through the intersection of culture and economics seems to become super charged by the high octane fuel propelling the varied components as they pass through the traffic.

As I have traveled to nearly every nook and cranny of this globe, and observed hundreds of people groups and the diverse examples of civilizations, I have been amazed at the human capacity to harbor and display the phenomenon of evil. I traveled throughout Rwanda on the heels of the terrible Hutu- Tutsi genocide. I was in Congo and Angola at the time of the mass murders. I personally viewed Pol Pot’s torture chambers located at the old high school in downtown Phnom Penh, Cambodia, and witnessed where hundreds of thousands of Cambodia’s best citizens were intentionally slaughtered by their own government.

I was in Bosnia, Kosovo, and Belgrade, Serbia and witnessed the atrocities taking place. In the little country of Nagorno Karabakh I watched the genocide by the Russian Fourth Army, the Azerbaijanis, and the Turks wipe out eighty percent of that small country’s male population, and it seemed that hardly anyone even noticed. I’ve spent time at the Holocaust memorials in Jerusalem, Israel, and Washington D.C. and asked the question, “Just how can this be?”

That same capacity for evil can likewise be observed in the law-ignoring greed of local governments, corporate heads, and homegrown community thugs, as well as even fraudulent social services recipients.

But, history has also shown that the folks gathered at the intersection can receive and contain a remarkable capacity for virtue. It is possible for them to attain through invitation and development, excellence of character. And based on that excellence of character, they can choose to become agents and dispensers of kindness, generosity, fairness, sympathy, mercy, personal responsibility, justice, charity, gentleness, forbearance, righteousness, and benevolence.

The individuals standing on the curbside of the intersection have the power and opportunity to ultimately determine history. But who will actually step forward and begin the process by taking the precious items from their market basket and injecting them into the flow of traffic?

As I visualize this epic scene of the making of history at the intersection of transformation, my mind recalls an intriguing episode shared with me by a new friend as I traveled through Asia:

Past the seeker as he prayed came the crippled and the beggar and the beaten.

And seeing them, the holy one went down into deep prayer and cried,

“Great God, how is it that a loving Creator can see such things and yet do

nothing about them?”

And out of the long silence, God said, “I did do something . . .

I made you.”

We who are standing on the curbside of the intersection of transformation have the power to influence the direction, timing, and outcome. How will we handle the opportunity?

Next Week: Vice vs. Virtue

© Dr. James W. Jackson

Permissions granted by Winston-Crown Publishing House