(Journal: L’viv, Ukraine: September, 1999) By that time, Meeche was down the corridor with the lead guard. The guard with the most stars on his epaulets gave a head motion to the man holding the door-opening mechanism. The top of the door had a steel bar that slid in a groove. The groove was positioned so that it was lower on the face of the door where the bar latched into the door casing. With the help of gravity, the latch always slid in a downward angle when being locked. Another sliding bar was located toward the bottom of the door. The guard always kicked that bar open instead of bending over to move it.

Once the top and bottom bars were slid into an open position, a strange mechanism that looked more like a socket wrench than a key was pushed into a square, steel-latch box and turned. The cell doors were solid steel plates but were covered with wooden strips to soften the appearance of the hallway.

Once the cell door was yanked open, there was yet another locked door with steel bars. It was quite an ordeal just to get into the cells. When the first set of doors was opened, it suddenly dawned on me what we were seeing. Meeche hadn’t indicated, nor had Lloyd, whether he knew that we were only visiting the hospital cells of the prison.

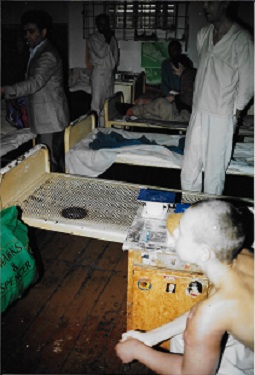

Once the doors were opened, the stuffy, stale, humid air came rolling out into the hallway. There was only one barred window in each cell, and the windows were tightly shut. Beds were placed in the cells so closely that they nearly touched. As we entered, nearly all the patients were asleep, which immediately raised my suspicions that the officials probably kept pretty good discipline through the liberal use of injected chemicals.

The first bed in the first cell held a young man in his late teens or early twenties. He had a strange-looking shoulder joint, and there were large nodes growing straight out from his shoulder. I bent over to take a closer look and then looked at the nurse. She indicated that I was in a cancer ward by whispering the word oncology. I pointed to the nodes, and she shrugged her shoulders as if to say she didn’t know. I decided to take a chance. I pulled out my camera and slid the flash attachment onto it. I looked into the woman’s soft eyes and motioned that I wanted to take a picture of the strange shoulder. She nodded her head in agreement.

Then the nurse pointed to the worn, soiled bedclothes the sick prisoners were wearing. I asked Meeche what she was trying to tell me. She wanted to know if we could bring clean gowns, blankets, and sheets. They had none. I pointed at the bedclothes with my camera and snapped a picture. The guards all looked at me when the flashes went off in the dimly lighted room. But none of them said anything because they knew the nurse was working with me.

By that time, many of the men were out of bed, standing up to receive the quarter loaf of bread, sugar packet, and candy from Meeche. With each disbursement, he also placed in the hands of the prisoners a small Bible written in Ukrainian. I kept snapping photos. I figured I would continue until someone told me to stop.

If I close my eyes, I can still see the looks on the faces of those pitiful, cancer-ridden, male prisoners as they received the gifts and the Bibles. My stomach turned as I looked in the corner of the stuffy cell. A two-sided wall stood about four feet high in one corner of the room, suggesting some sort of room division. I peered over the wall and saw the same number of red plastic pans on the floor as the number of prisoners in the cell. There in the corner was a sewer trap they could squat over to relieve themselves. I tucked my camera under my arm and worked my way toward the door and back into the hallway.

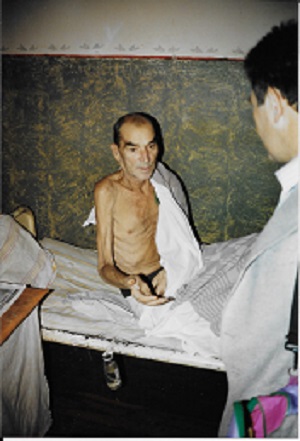

The next four or five cells were pretty much in the same dreadful state. The only difference was that as we proceeded down the corridor, the patients’ conditions were more severe. One man had a wad of gauze stuffed into a cancerous hole in his neck in an attempt to stop the drainage. The nurse indicated the middle-aged man had throat cancer.

I inquired about treatment for the cancer patients. She told me through Meeche that they didn’t have access to chemotherapy or radiation. I presumed that the cancer we had seen was pretty much the prisoners’ death sentence. I relished even more the smiles and hands clasped together in a gesture of thanks as the men received the bread, candy, packs of sugar, and especially, the Bibles. I thought to myself as I continued taking pictures of Meeche and Lloyd handing out the gifts, These men are on their own death row, no matter what crime they committed that landed them in this awful place. The only hope they have now will have to push its way off the written pages of the Bibles they are holding in their dirty hands.

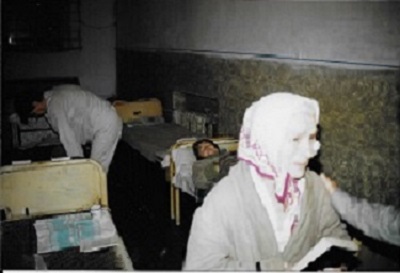

At the end of the corridor were two cells on the left-hand side. The heavy doors were bolted and latched just the same as those on the previous doors—first the heavy steel door veneered with wooden strips, then the steel door with bars. But behind such ultra security resided not men but women prisoners who had cancer. The first cell was filled with younger women. Some were in their early thirties. Some were too sick to even lift themselves out of bed to receive the gifts. I pressed my luck and kept on shooting pictures.

Some people say Ukrainian women are the most beautiful in the world, with their straight, proud postures, slender bodies, long legs, fine features, and fair skin. But those women, as young as they were, had been drained of everything in life but hopeless despair. They knew they were going to die in that cell. A couple of them had wild eyes like a frightened colt. But a couple of them could have been the mothers of my grandchildren.

The next room took the starch out of me. We were met at the door by an old woman wearing a faded, red scarf tied under her chin. She wore a ragged dress and was barefoot. A gauze pack covered most of the left side of her face from under her left eye to her jaw. On the table next to her dingy bed were metal food utensils with crusty soup in one and cloudy, tan water in another. When Meeche gave her the bread, sugar, candy, and Bible, the old woman melted into tears. She held on to Meeche’s arm as she sobbed. She reached up to wipe her tears away and put her hand back down when she ran into the gauze bandage. Lloyd handed out the rest of the gifts in that cell.

My heart was broken into tiny pieces. On this crisp September day, someone brought ten minutes of love to that old Ukrainian woman who was dying in prison with cancer. She had no way of telling that the autumn sun was warm today, or that there was a cool wind blowing gently, twisting and turning the oak and chestnut leaves and tugging at them until they fell softly to the ground. She had probably lost track a long time ago as to whether it was Tuesday or September or nearly a new millennium. But someone had entered that prison cell and opened those heavy steel latches so the love of God himself could pass over the steel threshold and wrap tightly around her in her lonely misery. I prayed that God would help her find truth, light, and hope and even a sense of freedom as she read the pages of the book she held so tightly in her hands. She was holding on to the bars of the inner door as the guard slammed shut the outer steel door with the wooden strips and kicked closed the bottom latch.

I don’t know what the old woman did to get thrown into that prison or just how long she has been there, but a feeling swept over me as I stood staring at the closed door that I would somehow like to take her place and let her go free.

Next Week: Why Help People You Don’t Know?