While we were bumping along in our little 4x4, Justin and I had quite a bit of time to process the things that were taking place during our trip to Colombia. We talked about how best we could continue to involve the students of Colorado Christian University in international awareness and ministry. He made some very insightful observations and suggestions for future involvement. He also expressed a strong desire to work for Project C.U.R.E. after he finishes his schooling. I challenged him to begin working now on the concept of finding an organization or group of supporters who will stipend his work for Project C.U.R.E. and encouraged him that the people at Project C.U.R.E. would consider it an honor for him to come on staff whenever he is ready if we can figure out the financing of the arrangement.

I am really excited and stand in awe at the way God is bringing just the right people at just the right time to assume the many tasks involved in the future growth of Project C.U.R.E. Apparently, God is really concerned that we continue the endeavors of bringing help, healing, and hope to thousands of hurting and discouraged people around the world. I believe he personally knows and cares about each of those hurting individuals and is somehow pleased to continue blessing and guiding the efforts of a humble, crazy organization called Project C.U.R.E.

At about 7:30 a.m. we left the parish house with Andrew and drove downtown to the archdiocese offices to pick up Vienne (pronounced “Vee-eh-na”), who is in charge of all social outreach for the diocese.

Vienne is very familiar with the barrios and the invasion cities near Montería. We left the center of town and drove north across an old metal bridge spanning the Sinú River; then we proceeded into what is normally swampland. Along the river, well over a mile long and three-quarters of a mile wide, were the strangest assortments of living shelters one could imagine. Whatever could be gathered together to make a front wall, a back wall, and a roof became someone’s house. It was all just an uncreative assortment of boards, tin, cardboard, and plastic. Many times there were no inside walls. The shelters just ran together, and the squatters arbitrarily staked out their claims under the protective roofs, sheet metal, and thatch.

There are thirty-two such invasion cities in Montería. The people there are the poorest of the poor. Many of the inhabitants are single mothers with four to six children. The term invasion city connotes the fact that many people at one time came rushing to the urban squalor looking for refuge from one major crisis or another. A high percentage of the people are there to escape violence or guerrilla warfare. Many of the husbands had been killed, and there was nothing left for the widow and children to do except move to the city, where the mother could possibly find work to keep her family together. But once there, the invasion-city dwellers find that there is nothing for them to do and no employment available. They then go into survival mode and try to exist on nothing.

The difference between an invasion city and a barrio is usually the fact that the invasion cities were built nearly overnight out of junk and trash. The barrio areas, by contrast, had some approval and sanction from the city to be built. The people in the invasion cities do not have any business being on the land they have invaded; they simply had to have a place to get their families in out of the hot sun and rain. In the barrio areas, the city usually gives the dwellers permission to build on the land or sells the land outright to the people for a small price. The shelters in the barrios are usually constructed out of gathered stones or concrete blocks. But the base level of abject poverty seems to be about the same in both the barrios and the invasion cities: no jobs, no money, no hope.

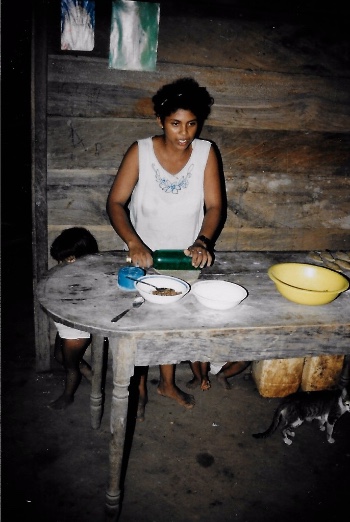

I went with Vienne into several of the squalid huts. The floors of all the invasion-city units were mud. With the heavy rains we have been experiencing and with the cities being built in a natural swamp area along the river, all the floors were soggy with standing water in the corners and outside. The sewage ran down the center of the makeshift roads or behind the huts. Pigs, chickens and ducks all did their best to forage for any scraps they could eat. I watched the precious little babies crawl along the floors through the mud and wondered to myself why far more of them don’t die from lung congestion and parasites.

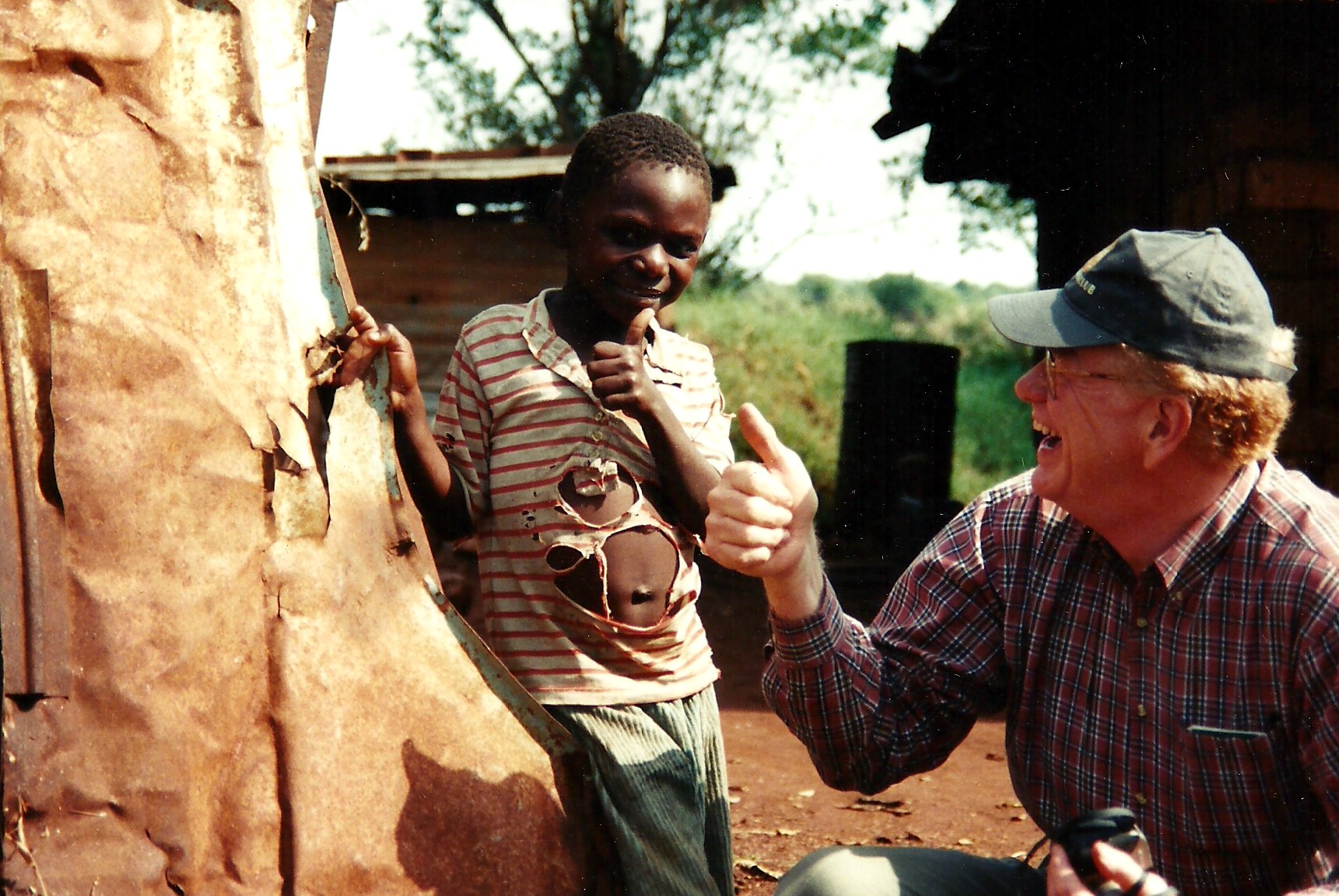

Over the years of observing some of the worst situations of misery around the world, I have somewhat been able to deal with the filth and poverty. But I can never get away from the thousands and thousands of empty eyes that even years later haunt me as they pleadingly look at me from their terrible conditions and register clearly as our eyes meet, “I have no hope.”

In Montería, it is not a situation where the people are just lazy, and the results of their idleness have caught up with them. Those sad humans moved to the city to escape some awful trauma, only to arrive and find themselves in an empty pit of hell that had slippery, slimy walls of swamp mud prohibiting them from ever climbing out. At times like this, I find myself with absolutely nothing to say because of the big lump in my throat and the feelings of absolute helplessness.

I know there is nothing I can do to socially, economically, or physically “fix” it. Then God seems to quiet my heart and say, “Don’t try to fix it. Just get home and send one more cargo container of medical supplies—just one more … just one more.”

Later, we visited and assessed a very large hospital in the city. You would have had to have been there to see and believe the impact and result. Both the doctor and the head nurse were nearly in tears; they just could not believe that someone out of the blue would make an appointment, view their hospital, and brag about them and encourage them in their work. Both of them just hugged and hugged and hugged me. Again, I thought to myself as we left, Certainly Project C.U.R.E. is all about saving thousands and thousands of lives around the world. But it is also about relationships with people around the world to bring help and encouragement to their little corners of the world. Once more I thought of the words of Dr. Vilmar Thrombeta in Brazil: “Mr. Jackson, you have brought millions of dollars’ worth of supplies and medical equipment to our hospital and university here in Campinas, Brazil. But the most important thing you have brought to us is hope!”

On this July 1, 1997, in mosquito-infested and drug-and-guerrilla-warfare infested Colombia, South America, Project C.U.R.E. has once again delivered hope—hope to a bishop, hope to his priests, hope to an entire hospital staff and administration—which could change lives forever. We have also successfully arranged for millions of dollars of donated medical goods to be delivered to Colombia, Belize, and many other Central and South American countries thanks to our United States Air Force and the skills and goodness of the crews of those huge C-130 and C-140 cargo airplanes.

I went to bed tonight the happiest man in the world.