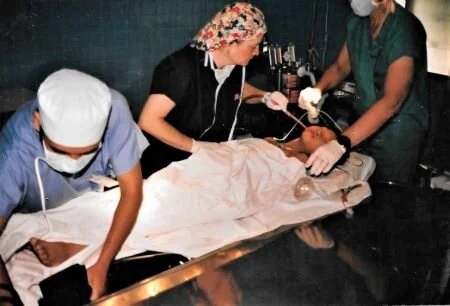

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: Tuesday, October 15, 1996: The next operation I viewed included Dr. Rennie Crane as the surgeon. He was assigned a patch-up job. His patient was a middle-aged man who had previously had a large facial tumor removed from the lower right side of his face. The tumor had spread to include the lower right jawbone. So during the former procedure, doctors had also cut away the jawbone. The previous surgery had to heal correctly before someone could go back in and replace the jaw. But how do you replace a jaw? You can’t just run down to the parts house on the corner and pick up a jawbone. So you have to be creative.

While Dr. Crane started cutting from below the Adam’s apple upward, one of the Vietnamese surgeons began opening up the patient’s rib cage. They apparently found the bone they thought would be just right and proceeded to hack and saw away until they had removed it from its lodging. Once removed, the bone was placed on a stainless-steel table, and Dr. Crane commenced whittling and shaping it into a jawbone. Satisfied with that step, he then went back to preparing the jaw to receive the new addition. Several hours into the operation, the looks on the doctor’s faces told me the procedure was getting more complicated than first predicted. The looks of doubt turned to frustration … lots of tension … lots of sweat. They kept opening the neck and jaw area up wider and wider, trying to get the replacement bone connected and situated right.

I remember thinking to myself, If I were doing the procedure, right about now I would be wishing that I were welding on a piece of farm machinery, and I could torch and cut and weld the piece of steel. And if I really messed it up or broke it beyond repair, I could just go buy a new part and start over again. But that guy was alive, and the pieces all had to work correctly when he woke up.

When Dr. Crane finally finished, the job was beautiful, and the jaw hinge worked wonderfully well.

During several other surgeries, I watched Dr. Randy Robinson, on two different occasions, remove ribs from children and carve them into shapes that looked like small butter croissants. He then surgically planted them on the sides of kids’ skulls to form the structure behind the outer ear. Those cases were where the children had been born without any ear at all on one side of the head. The rib bone build-up was the first step before taking other cartilage and skin pieces and making a new ear simply out of borrowed parts.

Dr. Crane was scrambling to get his patient stitched shut. We had all been invited to a luncheon banquet at noon by Dr. An and the staff at the institute. Lunch was held up a bit, but eventually we all got there. We were treated royally. Face the Challenge and Project C.U.R.E. were honored by the institute leaders, who not only gave us gifts, but more important by far, extended to us their feelings of deep gratitude.

They told Randy that many of the procedures and techniques that the institute doctors and staff had learned from Randy and his team over the past two years had already been passed on to the craniofacial surgeons out in the provinces.

Wednesday, October 16

Yesterday was the last day for the team to do surgeries. They had worked late last night to try to finish up on the agreed-upon cases. To start out the day today, the entire team met on the ninth floor of the Saigon Hotel for a time of devotions and a discussion of the plans to pack and prepare to leave Vietnam. We all then gathered on the big wooden stairway of the hotel for a final group picture.

At 9:00 a.m., a group of us headed to the hospitals to do rounds to check on patients. That served as a great opportunity for me to take some follow-up pictures of the patients I had seen go through the surgeries. We first went to the institute hospital. Every patient looked better than I even thought they would. As you might expect, there was some swelling, and some patients still required drains and bandages, but some of the cases I thought most difficult looked absolutely great.

The patients who were old enough to know what had taken place could simply not stop thanking the doctors. Many had made cards, which they gave to the nurses and doctors. Also, many of the parents had made little gifts of appreciation for the team.

I don’t know for sure … maybe the first day of heaven will be a little like that.

At 11:00, we made our way to the health-center hospital. I was able to see again the little, young couple and the seven-month-old baby boy we had seen in the recovery room. The mother was still gently rocking her baby as she stood singing the same lullaby tune I had heard the other day.

The health-center hospital had planned for a luncheon banquet today. They were so generous with their words and tokens of thanks. After the lunch and after finishing making the rounds, the team made sure that everything that is to go back to Denver was securely packed. All the supplies, most of the medicines, and all the equipment that Project C.U.R.E. furnished or Face the Challenge brought will stay in Vietnam to be used by either of the two hospitals or to be passed on to the provincial hospitals.

This evening was celebration and farewell time. We all walked from the hotel down to the river and boarded the restaurant ship Mermaid. We had a delightful dinner being tugged up the river and floating down.

Thursday, October 17

Between the time of the river dinner last night and our departure for the airport this morning, almost everyone to the person asked for information about Project C.U.R.E. and how they could get involved. When I explained to them that our goal is to have between twenty and twenty-five Project C.U.R.E. warehouses placed in strategically located medical cities, many volunteered to be part of organizing a warehouse operation.

At the airport I parted ways with the team. Their tickets will take them to Los Angeles via Singapore. They will stay on layover one night in Singapore. My ticket will take me to San Francisco via Hong Kong and then straight to Denver. That makes an extremely long trip out of it, but I am ready to get home to some crisp, clean sheets and then on to the work that has been piling up in the office. In just several more days, I will be re-packing my travel things and hopping on another jet that will deliver me to Ethiopia. I thank God for all the opportunities!