Ho Chi Minh City (Old Saigon): October 14, 1996: My alarm rang at 5:15 a.m. I wasn’t sure why, except for the fact that I had set it for that time while I was still in my right mind. But I was certainly far from my right mind that early in the morning. The bus had been scheduled to leave the hotel to go to the hospital at 7:00 a.m. sharp. Dr. Randy Robinson brought surgery-room scrubs along for me to wear so that I can be in the operating room for the procedures. That will not only allow me to get better acquainted with the twenty-five-member team but will also allow me to take my camera into the operating room and get some pictures of the actual procedures.

Plans were made to work simultaneously at two different hospitals. One hospital is called the Institute of Odonto-Stomatology located at 201A Nguyen Chi Thanh Street. Its director, Dr. Lam Ngoc An, is a very gracious man and prepared well for the team’s appearance. That hospital is connected with the university medical school that teaches cranio-maxillofacial procedures and plastic surgery. But even with the doctors they are turning out from the institute, there is still a backlog of over seven thousand children with hair lip and cleft palate in Vietnam who need surgery. Also, there are hundreds of adults who are deformed, never having had access to medical procedures. Dr. An and Dr. Huynh Dai Hai and the other professors and doctors are doing the best they can to catch up to the situation.

The second hospital is referred to as the health center, directed by Dr. Khoi. This morning the team was divided into two groups, half going to the institute, and the other half going to the center. Dr. Randy Robinson and Dr. Barry Steinberg were the surgeons at the center. There were two operating theaters prepared for the team at both hospitals. So, every day the team was there, four surgeries were going on at the same time.

I decided to go with the group to the health center to start my day. While we were waiting for the first patients to be brought in, Randy took me around and showed me where they had put all the supplies from Project C.U.R.E.

On one of the days before my arrival, the team had unloaded the shipping cargo container and sorted and divided the materials between the two hospitals. The team was overwhelmed that we had sent so much good, good “stuff” along. I was able to take pictures of the medical supplies that were stacked not only in the operating-room supply area but also in a separate storage area of the hospital complex. Project C.U.R.E. had sent well in excess of $300,000 worth of medical supplies in that load.

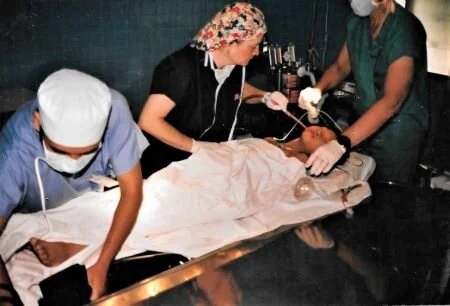

When the operations got underway, I was able to walk back and forth between the two theaters and take photos of both procedures taking place.

Dr. Barry Steinberg is one of Randy’s professors at the University of Michigan Medical School. He holds PhD, DDS, MD, and FACS credentials. He is still director of the residency program at the University of Michigan, where he teaches, and is also chief of service at Mott Children’s Hospital. Dr. Steinberg is not only smart; he has some very gifted hands.

His first patient was a ten-year-old girl. She was very badly disfigured and should have had surgery when she was a baby. She had a hair lip, a severe cleft palate, and no functional nose on the left side. I watched with amazement at how Dr. Barry restructured the girl’s face.

The procedure was complicated enough that while Dr. Barry was working on the face, Dr. Randy opened up the girl’s hip, chiseled out some hip bone, and scooped out quite a large amount of bone marrow. He told me that when they need bone material like that, they usually take it from the hip, the ribs, or the skull.

In order for Dr. Barry to close off the cleft palate, he had to restructure the roof of the mouth and then pack in the bone marrow all the way out to the gums and nose area. He then took larger pieces of bone chips and formed a functional nose. He told me as he was packing in the bone marrow and forming together the bone chips, “Jim, you have to make sure that all this new material connects, because the healing agents can swim … but they can’t fly.”

He opened then, for the first time, a passageway for airflow on the left side of the nose. The operation took about five hours, but when Dr. Barry stitched her all shut, I could hardly believe that it was the same little girl.

As I watched, I could only imagine the difference this surgery is going to make in that child’s life. Of course, she is never going to be as perfect and beautiful in features as, say, one of your grandchildren, but now she will be able to breathe and eat normally and will probably marry and have a family of her own.

While Dr. Barry continued operating in one room, Dr. Randy proceeded with his surgery in the other room. He was working on a precious little baby boy, less than seven months old. The condition was a double hair lip. It was really quite grotesque.

I remembered seeing the young mother holding her baby when we went to the ward and Dr. Randy had done a pre-op check. There was fear in the mother’s eyes as she gave the baby to Dr. Randy to hold, but with her entire face, she was almost pleading for someone to do something about her ugly but precious little baby. The baby could not suck, so the mother had to extract the milk from her breast and spoon-feed it, being very careful that it did not spill into the air passageway and drown the child.

I noticed that Dr. Randy had taken his pen and drawn a mouth diagram on the surgery drape on the baby’s shoulder. He then took a surgical pen and made reference dots on the baby’s face. I thought as I watched him that he is not only a skilled surgeon, but he also has to be an artist, visualizing a perfect mouth all the while he is cutting and stitching that little face.

The center one-third of the upper lip simply did not exist, but down from where the lower part of the nose should have been was a single piece of bone jutting out and looking as if a single tooth will protrude from it someday. From the corners of the mouth upward, there were two very short sections of lip coming from each side. Then the normal part of the lip turned into two large bulbs, each almost the size of a regular baby’s nose. It was quite clear to me that the center had given to the visiting team their most complicated cases to fix.

I watched Dr. Randy and a woman from Florida, Cindy Surmaczewica, his attendant nurse for the day, as they worked like clockwork together. Cindy almost knew what Dr. Randy was going to do next. There was a tremendous amount of concentration taking place, and you could feel the intensity of the situation with each slice of the scalpel and each stitch of the curved needle.

When it came time for Dr. Randy to make new lip pieces to fill in under the restructured nose, he slit open the large flesh bulbs and began carving the tissue out of them and stretching them across to join beneath the nose. It was not just a surface procedure that took place. The skin on the outside must all fit together, but so must all the pieces of tissue and muscle underneath the skin. Likewise, the inside of the mouth must be restructured correctly, as well as the outside, and the new lips must be secured to the gums as well as to the base of the nose structure.

After more than four hours, the job was really beginning to look incredible to me, but Dr. Randy was not quite happy with how the last part was coming together. So he unstitched part of what he had done and reformed the little lip until it came together and matched up perfectly.

Dr. Barry Steinberg’s patient had been moved into the recovery room and was waking up. I imagine that the ten-year-old girl is not only going to have an extremely sore face for a while, but she is also going to have to put up with a sore hip where the bone had been removed. It would be quite an experience,

I suppose, if I could tap into her thoughts the first time she looks into a mirror and sees that she has a nose, and the first time she experiences swallowing without the water coming out the front of her face. At age ten, she certainly is old enough to never forget that doctor who loved her enough to come all the way from America to Vietnam to make her beautiful.

With the first surgeries finished, we all went to the breakroom and grabbed some bread and cheese and junk food. Then we scurried off to meet with Dr. Khoi and the other hospital officials. They had arranged for a meeting and had invited the TV cameramen and press. That was the first time I have ever done an interview while wearing operating-room scrubs. I did get my mask turned around and my cap pulled off, but I looked down and noticed that I still had my booties on. However, no problem, because the other Americans looked the same way.

Next Week: Miracle Workers in the Operating Theater