Friday, February 6, 2004: Kinshasa, Congo: I think the Sthreshley family was trying to spoil me because for breakfast they had fixed peeled grapefruit and real French toast. What a delight after eating rice and leftover chicken or fish for breakfast up north.

The lung and sinus congestion that I had brought with me to Africa had gotten worse in the Congo. By Thursday night I had started to run a fever. Fortunately for me, I had toted along in my suitcase some biaxin, a strong antibiotic product for such problems. I knew I should not take lightly what I was feeling starting to happen. Pneumonia could be a killer in the Congo.

Larry and I started talking seriously about Project C.U.R.E. Friday morning. After spending time with him previously in the Congo and Cameroon, assessing his work and the Presbyterian hospitals and clinics there, Project C.U.R.E. had sent to him nearly $2 million worth of medical supplies and pieces of equipment for his institutions.

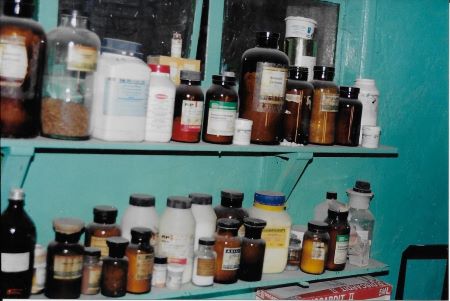

He wanted to take me to his warehouse in Kinshasa to show me how he was handling the distribution of the goods. When the cargo containers arrived he and his people there would break down all the pallets and big boxes and inventory and stack all the separate items on shelves in his warehouse. From there he would send out or take the needed supplies or equipment pieces to the individual Presbyterian hospitals from his stock.

Dr. Murray, with whom I had met and traveled before, was working with Larry checking out all the pieces of equipment. Recently, they had visited the hospitals and clinics and determined where they were regarding their specific needs and what level of medical expertise could be found at each institution.

I was thrilled. Larry was performing a “value-added” service to everything Project C.U.R.E. was sending and greatly enhancing our effectiveness and success. I told him that I would like to see his same model rolled off into Malawi, Kenya, and Zambia where his Presbyterian counterpart, Frank Dimmick, was located.

We raced from the warehouse back to Larry’s office where Rev. Mossi and Mr. Ndimbo were waiting to escort me back out to the Kinshasa airport.

At 11:05 a.m., I was to take Cameroon Airways flight #817 from Kinshasa, Congo, to Douala, Cameroon. Pastor Mossi and Mr. Ndimbo were going to see to it that I would be on that flight. I told them how much I appreciated them and that it really made a difference to have a local get me through the African airports so I could avoid all the hang-ups and bribe attempts.

Flight #817 from Kinshasa to Douala was only about an hour and a half long, but it took about the same amount of time in Douala to unload and return my checked luggage. I recalled all the years when I never took anything I had to check in. But since September 11, 2001, everything had changed. Now security measures in both the US and internationally had made it impossible for me to travel without checking certain things through.

At the Douala airport the workers knew that I was not going to leave without my luggage so there really was no need to hurry and get it delivered to me within any given time frame.

I was met at the airport by a Canadian missionary named Dale but was quickly handed off to a sharp, young, black national named Vincent. Since it was late in the afternoon and the trip north to Mbingo was a very long one, Vincent delivered me to another missionary guesthouse just across the street from the port and docks in Douala.

While eating with Vincent, I asked if there would be any possibility of meeting with any government or shipping people who could help guarantee our success in getting our containers into Cameroon without problems and without getting gouged with shipping fees, duty, or taxes.

Later, Vincent rounded up and brought to where I was staying a roly-poly local man named Tim Francis. Tim ran his own company and specialized in receiving shipments through the ports and all the government officials. I found Tim to be a wonderful and warm Christian who was dedicated to helping the Baptists get their cargo shipping containers into Cameroon successfully. I told Tim that my old granddad had taught me that it was easier to stay out of trouble than it was to get out of trouble. I was there in Cameroon before I shipped anything into the country for the Baptists so that I could stay out of trouble and be successful, rather than getting one of my valuable medical loads tied up in customs or with the port authorities.

Tim thanked me for my approach and said he wished every shipper would be as dedicated and efficient. He then pulled out of his briefcase files showing me exactly what I needed and how to word the different letters and forms. It was important to use certain words in the official letter of donation, as well as the request for tax exemption.

Tim was a real answer to prayer. I had fretted and stewed all the previous week wondering how we would ever deliver the medical goods to the far north of Congo. In Cameroon I now had an ally who would help us. Tim had been able to do through the Cameroon government what Larry Sthreshley had never been able to do in Douala or Younde.

Before parting ways, I asked Tim if I could count on his help if I had problems with getting my loads into northern Congo. I had been thinking all last week of the possibility of shipping the Congo loads into Douala, Cameroon, and taking them across Cameroon and the Central Republic of Africa, then directly into northern Congo since there were no roads to Loco, Wasolo, or Karawa from Kinshasa.

Tim thought that just might be the way to ship and promised he would help Project C.U.R.E. try to accomplish it.