Saturday February 24, 2001: Hargeisa, Somalia: As I was getting ready to leave my room this morning, I was almost overwhelmed by what I had read about and seen in Somalia. Even as I slept, my mind continued to process the experience. During my private devotions last night, I specifically asked God to give me wisdom and favor for the hours I spend in Somaliland. I haven’t traveled to many other places with so much historical grief and apparent need. I somehow feel that if handled wisely, Somalia could be an incredible example of what Project C.U.R.E. can do for a hurting nation by the grace of God.

At 8:30 a.m., I was in the office of the minister of information. His people then covered my meeting at the office of Hargeisa’s mayor at 9:30 and began broadcasting the information about the arrival of Project C.U.R.E. on national radio and television. By that time I was becoming well-acquainted with both the mayor of Hargeisa and the minister of information.

The minister of health, Dr. Abdi Aw Dahir Ali, arranged for us to meet in his office building at 10:30 a.m. There I explained exactly what Project C.U.R.E. wanted to achieve during the hours of the visit and told him that I needed his wise counsel and the cooperation of his hospital directors and staff. I explained my needs assessment, and he briefed me on the condition and organization of the health-care system in Somaliland.

By 11:15 a.m., our entourage had moved down the street to the Hargeisa regional hospital. The director of the hospital, Dr. Deq Jama, was extremely embarrassed about the condition of his hospital and was afraid that I had come to Hargeisa to ridicule the hospital and his efforts. Eventually we worked through the barriers, and he opened up about his needs and concerns.

The hospital facility was erected during the British colonial period and is laid out in a campus style with each department, ward, and service in a separate building. The complex looks pretty good from a distance (say about ten miles). All the buildings are brownstone and are surrounded by a high compound wall.

The real shock came as we entered the buildings. Everything was destroyed or stolen during the war years. And in the ensuing years, the hospital had neither money nor friends to help rebuild and restock it. It’s the primary referral hospital in the region, which means that any cases that can’t be handled in the outlying areas are referred there. The only problem is that, in theory, they handle all treatments and specialties as the ultimate end provider.

In the administration section, I never spotted even one typewriter or business machine. All patient files, billings, correspondence, and other documents are written out by hand on random scraps of paper. Some of the personnel know how to type; they just don’t have any equipment.

As we visited the examination, trauma, and emergency departments, I was told they don’t even have suture materials or proper wound dressings. Examinations are performed on old wooden tables, and the staff members desperately need lights and the most simple instruments. I kept thinking, This is the best hospital available here for a population of about six hundred thousand people. How do they cope?

Two ancient X-ray machines were in the radiology department in dismantled pieces on the floor. One prisoner in chains was having his ankle X-rayed by the only machine in the region. It was an old, old portable Japanese machine about the size of a shoe box. I doubt it was more than 25 to 50 milliamperes (mA) and hardly strong enough to view a bone.

Sometimes in the old Soviet Union, the hospital directors tried to sandbag me. That is, they would show me their worst operating room, which was mainly dysfunctional, and then tell me that was the best they had. They hoped that by impressing me, Project C.U.R.E. would give them all new equipment. But I don’t sandbag too easily!

When Dr. Jama showed me his operating theater, I was tempted to think that he was sandbagging me. I wanted to probe the situation until he showed me the functional theater. But in Hargeisa, no sandbagging was going on. There was no anesthesia machine anywhere. There were no overhead lights; no ventilator, respirator, or defibrillator; no monitor; no bright, shiny instruments—nothing but an antique operating table, an empty cabinet where supplies used to be stored, a broken suction machine, and an old pressure cooker placed over an open fire to sterilize their old surgical instruments.

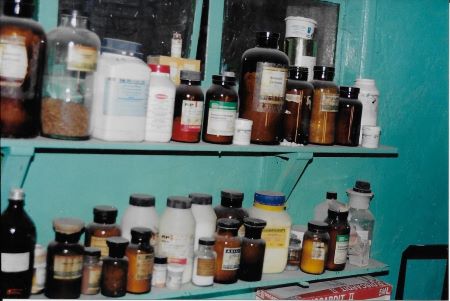

The laboratory was equally shocking. Their microscope had been shattered, and they were all out of reagent, so even the most simple blood or urine tests couldn’t be performed.

“For diagnosis,” Dr. Jama told me, “we are forced to guess a lot.”

As we toured the hospital compound, we walked past a building with a sign that read Rehabilitation and Therapy. I asked if they were doing any kind of physical therapy for people who were still losing legs and arms from exploding land mines left over from the war.

“Oh no” was the answer. “Those buildings are full of people who have gone crazy because of the terrible war.”

Families whose loved ones had been murdered right in front of them by scores of savage soldiers are still traumatized ten years later. Military men whose commanding officers had forced them to commit heinous crimes, and people who had witnessed their own government destroy hundreds of thousands of innocent citizens simply hadn’t been able to handle it mentally. Most died during the years following the war, but the delayed stress and post-traumatic complications left many incapable of living on their own.

Ninety percent of the pregnant mothers in Somaliland deliver their babies in their own homes with the aid of friends acting as midwives. They only go to the hospital if there is a drastic complication. So a very high percentage of those who do go to the hospital end up dying or at least losing their newborn babies.

Since so many mothers and babies have died at the hospital, it has a bad reputation, and the mothers say, “Why would I want to go to a hospital to have a baby? People who go to the hospital die there.”

Four mothers died recently at the hospital. One died simply because she hemorrhaged, and the doctor had no suture materials or emergency blood supplies. In Project C.U.R.E.’s warehouse, we have lots of suture material and plenty of blood-transfusion supplies.

When I said good-bye to Dr. Jama and left the hospital, I physically felt as if someone had put me in a huge vise and squeezed all the oxygen and energy from me. One thought kept racing through my mind: Those people had nothing … nothing. How can they continue each day knowing that the supplies exist somewhere, but they just can’t get access? I know Project C.U.R.E. can make a revolutionary difference in Hargeisa if we can begin delivering donated medical goods to their hospitals.

I’m becoming quite good friends with some of the government leaders in Somaliland. This evening I was invited to visit the home of Mayor Awl Elmi Abdalla for a friendly chat and some tea and biscuits. From the mayor’s home, Mohamed and I drove to the home of His Excellency, the minister of information, for a quick social call. His Excellency has a unique home and some unusual pets, one of which is a young lioness that was chained close to the front entry as a “guard dog.”

Next Week: Make Sure Your Driver is not on “Quat”!