Morogoro, Tanzania: Thursday, May 18, 2006: Thursday was sort of a happy/sad day. It was happy for me because I was one assignment closer to getting to leave Africa and return home to Colorado. Only Anna Marie and the Lord would know and understand how strongly I loved to head for home. And that was because they had both extensively traveled with me to some of the toughest places in this world.

It was a sad day for me because I was going to be leaving my new friends with whom I had bonded so quickly. Over the years I had learned to reconcile within myself that probably I would never return to the same place, and even if I did, expect to see the same people I had been with on the previous visit. It was simply impossible to place your feet twice in the same river.

I used to leave some place in Uzbekistan, Russia, Argentina, Serbia, or Guatemala and fully expect to, one day, return and greet my friends once again. But it had become obvious to me after traveling internationally since 1979 that chances are almost 100% that I will never meet again on this earth the hundreds of thousands of people I met and with whom I had shared love and friendship. I would simply have to look forward to the first million years in heaven to renew those friendships.

I was leaving my Catholic friends of Tanzania at the base of Mt. Kilimanjaro who had so graciously and unselfishly included me and showered me with every bit of love within them. Yes, I would miss them.

At breakfast I could tell that some sort of pecking order was taking place to see just who was going to get to fill the seats in the van that was to deliver me to the Kilimanjaro airport. I smiled to myself and thought, “This is so absolutely pretentious!” And even now as I relate the Kilimanjaro episode in the journal entry it all sounds too pretentious doesn’t it?

The clouds had drooped over and around the entire profile of Mt. Kilimanjaro for most of the time I had been in Tanzania. But Thursday morning there was not a cloud in the sky, and for our entire trip as far as Arusha, the old, snow-capped mountain straddling the African equator could be seen in its full beauty. I couldn’t remember any other time I had been in Tanzania and had such an unobstructed view of the profile of Mt. Kilimanjaro.

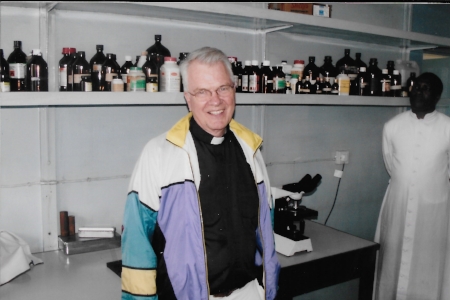

I had really appreciated the opportunity to get acquainted with Father McCormick. I could hardly wait to get home to Denver so that I could meet with his brother Dick and others in the family and relate to them how very proud they should be of Jim’s nearly 20 years of mission work in Tanzania. He had been a blessing those long years, and his example was still an inspiration to those of us who were just getting acquainted with him.

My Precision Airways flight landed on time at the Kilimanjaro airport and after lots of warm goodbyes I was off in flight back to Dar es Salaam.

At 1:30 p.m., I was hoping to be met by Father Shabas at the Dar es Salaam airport. He was there with another one of his friends, Father Malan. Father Shabas explained to me that Malan’s name was spelled with a letter “r” as in Marlin but the letter “r” was silent so his name was Malan … spelled “Marlan.”

“Okay,” I said. “I’m so glad to meet you, Father George.”

I had been introduced to Father Shabas while he was in Denver, Colorado. Father Shabas was an Indian, born in the southern section of the country. He had decided to become a Catholic priest and had asked to be sent to Africa as a missionary. Some folks whose home was in Colorado had been traveling in Tanzania. They had invited Father Shabas to come and visit them in Denver.

While Father Shabas was in Denver, he met Father Hoffman, the pastor of the Church of the Risen Christ located on South Monaco Street. Father Hoffman was a well-loved priest in Denver and was quite influential in the Catholic community. Father Hoffman asked if Father Shabas would be interested in staying in Denver and assisting him at the Church of the Risen Christ. The decision makers of the archdioceses smiled on the whole idea and for nearly three years, Father Shabas took leave from his mission work in Tanzania and served in Denver.

One day a friend from my past dealings in real estate in Denver, Mr. Sam Perry, called me and asked to get together for breakfast and meet this needy priest from Africa. When I went to the meeting I took Douglas with me. We both expected to meet a black African priest. Later, we all met at the office of Father Hoffman and learned further about the Holy Cross Sisters and their medical work in the area of Morogoro, inland, and almost directly west from Dar es Salaam.

Father Shabas told us about the work of the sisters and also the Carmelite Friars. Most of the leaders of the orders were missionaries who had come from India. They served under a black African bishop, and many of the priests and sisters were African, but the real energy and leadership was being engineered and facilitated by the dedicated folks from India.

I was intrigued by the mission work and promised Sam Perry, Dick Campbell, and other laymen in the Denver archdioceses that Project C.U.R.E. would love to go and assess the situation and see what could be done in Tanzania.

It took us over two years to put the trip together. The Knights of Columbus, a Catholic organization in Denver, even raised some money to aid the project. It was a natural conclusion to try to coordinate both projects in Tanzania with one trip – one for Father Jim McCormick and one for Father Shabas.

Actually, before we were able to set final plans for the trip, Father Shabas’ time in the US had ended and he returned to Morogoro. But that would make it more effective to have him there to host me for the Holy Cross Sisters and the Carmelite Friars.

We drove through the crowded, dirty, unorganized outskirts of Dar es Salaam toward the main junction of highways. One highway led to Morogoro City and the other back to the area I had just left. I certainly didn’t want to start driving back to Moshe, Kilimanjaro, and Arusha. I had just flown from there.

The highway was lined with parked transport trucks. Thousands of “rat trap” businesses had sprung up along the truck routes on the outskirts of the city. One of the biggest businesses was that of prostitution. Everywhere the truckers pushed their big rigs across Africa, they nurtured and supported the plague of prostitution and HIV/AIDS. It seemed that the truckers always had spending money and the desperate young women always needed the money. But the African society certainly didn’t need all the evil and ills that accompanied the truckers’ culture.

The huge trucks had completely blocked the entryway of a small drive that led from the highway toward a gated complex. Father Shabas had to vigorously use the horn of the Land Cruiser to get the people and trucks moved out of the way so we could exit the highway.

Almost swallowed up by the roadside crowds was a Catholic enclave consisting of a church, a school, and a home for the priests of several nearby parishes. We would be stopping there to meet some of the fathers who had kindly invited us to take a belated lunch before we traveled on to Morogoro.

The thing that once again surprised me was that all the people I met were Catholics who had agreed to come as missionaries to Africa from India. Only the head superintendent of the schools, Mr. Adam Kagoye, was a black African. But the principals of the schools were sharp Holy Cross Sisters and the priests were Carmelite Friars.

The Fathers who had gathered to have lunch with us were very intelligent, high-energy, sharp young men who were very focused on what they were doing in their mission work. Needless to say, I was very impressed and felt that I had received a huge and valuable insight that day.

I would be returning to Dar es Salaam on Saturday night to stay with the diocesan members. So I really enjoyed getting acquainted with them.

We were back on the road again. It would take us about three hours of hard driving in the heavy traffic to make it from Dar es Salaam to the mission station at Kihondo. As we approached Morogoro we pulled off the highway and through the iron gates of the Carmel College. It was a Carmelite Theological Seminary, which had just been built in 2002 and was run by professors and priests from India. They wanted us to join them for tea and get acquainted. The seminary students had mostly already gone home since the classes had ended for the year. The previous Friday had been the last day of the final examinations.

From the seminary we were scheduled to go to the convent of the Holy Cross Sisters and meet Sister Mary Jo and Sister Bindu, two more sisters from India who were helping run the Kihondo Holy Cross Dispensary. My communication in setting up the Tanzanian trip had been with Sister Mary George, the director, but she had been scheduled away from the convent and the dispensary during the days that were finalized for the May trip.

A lovely Indian curry/African dinner had been planned for us at the convent. It was getting late and I was asked if I wanted to proceed with the needs assessment at the Kihondo Holy Cross Dispensary that evening or wait until Friday morning. I opted to proceed with the assessment that night.

The sisters helped me answer all the questions and then took me on a tour of the facilities. The Holy Cross Dispensary served a population of 100,000. Just recently the government had closed one of the area hospitals. That was putting a strain on the under-equipped, under-staffed, and under-supplied institution.

The desire was to get the dispensary upgraded to a full health station and then push for qualification as a “hospital.” But to receive that qualification they had to meet requirements for their laboratory, procedural rooms, operating theaters, etc. They simply could not afford the necessary items that would help them achieve the status. They were really counting on Project C.U.R.E. to work a miracle with God’s help.

The humble little dispensary would need lots of medical goods if their dreams were to be realized. But the sisters and fathers from India had a plan and had the energy and desire to see it accomplished. I liked what I was seeing.

It was late. Father Shabas took me back over to the seminary and put me in a vacant room of an absent seminary student. Once again, the designer motif was very primitive, turn-of-the-century, (which century certainly wouldn’t make any real difference), peasant, abbot accommodations. But at least it did come equipped with a mosquito net!

Next Week: Come on London and USA!