Kilimanjaro, Tanzania: May 13, 2006: There were two separate requests for needs assessment studies that had come to me from Tanzania. They had been processed through our headquarters office and finally passed on to me with travel dates.

The first was a request that we had been working on for about a year. The Risen Christ Catholic Church in Denver supported a hard-working and bright priest who was doing missionary work in Tanzania. His name was Father Shabas, and he was requesting help from Project C.U.R.E. for the medical hospital and dispensaries run by the Holy Cross Convent in Morogoro, Tanzania. Sister Mary George was the mission superior for the East Africa delegation. She had also joined Father Shabas in the urgent request.

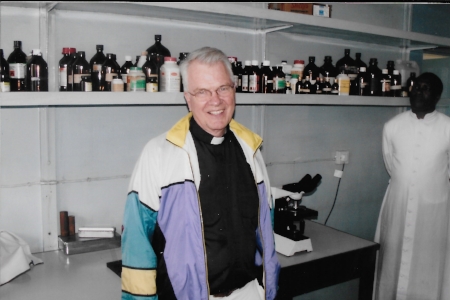

The second request, likewise originating out of a Denver concern, had come from Father James McCormick, a priest serving in Omaha, Nebraska. Father Jim had been born and raised in Denver as a member of a very prominent Denver family. During his years of mission work in Africa as well as the US, Father Jim had become aware of some acute needs in the Tanzania: in Kilari, Sanya Juu, Kibosho Rauya, Huruma, and Kilema in the Kilimanjaro area.

In Denver I boarded United Airlines flight #246 to Chicago where I connected to United Airlines flight #928 to London’s Heathrow Airport. Following a bit of a layover I made my way to Heathrow’s Terminal No. 4 area where I wearily made my way onto British Airways flight #47. I settled in with my pen and writing pad. The flight from London to Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, was a full, 10-hour, non-stop trip.

Sunday, May 14

As we flew along at 40,000 feet in the air I suddenly realized that it was Sunday. It was Mother’s Day. And again, I was somewhere halfway around the world and away from Anna Marie, the mother of my two incomparable sons. I was so very proud of my family and realized the price that we all had paid by choosing to pursue goodness and helping needy people all around the world.

I landed in Dar es Salaam on Sunday morning at about 6:30 a.m. Eventually, I transferred to a propeller-driven airplane and left Dar es Salaam on a flight to the Tanzanian city of Kilimanjaro where I was finally picked up by Father Jim McCormick.

The British Airways flight from London landed in Dar es Salaam about 25 minutes early. I was toward the front of the line to collect my luggage and clear passport control and customs. I had quickly spotted where I was required to re-check my bags on Precision Air for the next flight leg. The fellow who was in charge of the transfer seemed to be in quite a hurry to get my bags and give me my luggage receipt. I never gave it too much thought because I knew I had a long layover in Dar es Salaam. My scheduled flight was to have left at 12:30 p.m. and arrive in Kilimanjaro at 1:45 p.m. So, I knew I was in no hurry at 7:30 in the morning.

However, the London plane had arrived just early enough that the morning flight on Precision Air had not yet taken off for Kilimanjaro. The transfer agent had taken my bags and quickly arranged for them to be loaded on the early flight without my knowing what was taking place. I had just found a comfortable place to settle down and do some paperwork. The transfer agent came running up to me, “Mr. Jackson, the flight to Kilimanjaro is loaded and they are waiting for you to board. Your luggage is on the plane and they cannot leave without you on board.”

“I am terribly sorry,” I said with a twinkle in my voice. “Show me to the plane.” It really made little or no difference to me whether I sat in the Dar es Salaam airport for the nearly six hours or the Kilimanjaro airport. I suspected that the Kilimanjaro airport would be a little quieter and more conducive to writing anyway. Again, I had a good lesson that if you are not willing to be flexible and roll with the punches on international travel you should really stay at home.

I was, indeed, able to get some necessary paperwork done before Father Jim McCormick arrived to the Kilimanjaro airport about 2 p.m. to pick me up.

Along with him in the 12-seat van were six nuns from the Holy Spirit Sisters Convent in Sanya Juu near the city of Moshe. They didn’t want to miss out on a thing, and they had been waiting for over two years for Dr. Jackson to come to their medical facilities.

To fill up the other seats in the van were Father Jim McCormick’s sister-in-law, Betty Jo McCormick, and her university professor daughter, Catherine. Jim’s brother, John, had recently died, but while living in Wyoming for many years he had supported the missionary work of his brother, Father Jim McCormick in Tanzania. The two ladies had always wanted to see the work of Father Jim and the Holy Spirit Sisters.

It was a sort of joyous reunion. The sisters were singing and clapping. Father Jim had been the parish priest for the sisters for nine years. Then, for another nine years he had lived in the bishop’s house located on the large Holy Spirit Sisters Farm and Training School while he was traveling to other diocesan locations throughout Africa.

Father Jim told me at a later time that after the 18 years in Africa he had been ready to move back to the US to be “re-culturalized” into America. The church then had assigned him as pastor to a large parish congregation in Omaha, Nebraska.

Sister Elizabeth was our van driver. When we finally reached the large, 1,000-acre compound she pulled up in front of the iron gates. She then began beeping the van’s horn in a steady, four-beat rhythm.

I thought to myself, “Good Lord, lady sister, ease up on the honking. They probably heard you honk when we drove up and are on their way to unlock the gate.”

But Sister Elizabeth’s constant beeping had nothing to do with her patience or lack thereof. After at least two solid minutes of beeping, which seemed more like two hours, I caught a glimpse of some movement at the curve in the entry driveway just beyond the brightly colored bougainvillea bushes. One, then two, then a total of about ten black African nuns were dancing and singing and clapping to the rhythm of the beeping of the van’s horn and the accompaniment of another sister beating on a drum made from the cowhide of one of the farm’s former Guernsey milk cows. The hide was tightly stretched over a home-made set of metal rings and the sister beat on the hide with her bare hand, and was pounding on the metal framework with a simply-fashioned drumstick. The reception was a sight to behold!

When the iron-gate was unlocked Sister Elizabeth managed to steer the van with one hand and continue the beeping of the horn with the other. As the parade moved along the dancing nuns showered us with flower petals from the colorful gardens nearby.

As we pulled around the curve in the drive there were more singing, clapping, and dancing sisters. The driveway was moist from the recent jungle rains or otherwise the sisters would have created a dust storm of large proportions.

Little did I know that the excitement that had been created for our arrival would be a forecasting symbol of the spirit of love, energy, and appreciation for the next few days to follow. The fresh flowers the sisters had woven into the iron works of the entry gate seemed to represent the meaningful bond that would be intertwined around and through the hearts of the current residents and the newly arriving visitors.

The gleeful entourage waltzed us right into the dining room where we were served “high tea.” The Catholic group of Holy Spirit Sisters had been encouraged to purchase the 1,000-acre parcel of rich, fertile land in the early l960s as I understood it. Following high tea, the sister superior was eager to join Father Jim McCormick in extending to me the grand tour of the farm.

Next Week: Oh, Those Incredible Nuns!