Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: April, 1998: In my previous journal entries about Vietnam, I mentioned Binh Rybacki, a native of Vietnam who was one of the last to be plucked off the roof of the American embassy in Saigon in a spectacular rescue effort as the Americans were retreating from the city in 1975. There isn’t even the slightest shadow of a doubt that had she not been on that helicopter chopping its way to safety out of South Vietnam, the Communists would have killed her, along with all the other American sympathizers who were left as we withdrew in shame and frustration.

But Binh is still in love with her mother country and its people, even though her permanent residence is with her immediate family in Colorado. Over the years Binh has done a heroic job of reentering Vietnam and taking on the responsibility of caring for thousands of orphaned and disabled Vietnamese children. Binh’s organization is called Children of Peace, and she has orphanage facilities under her direction in the Ho Chi Minh City area in the south, as well as the Hanoi area in the north. She remains a computer engineer at the Hewlett-Packard enclave north of Boulder, Colorado, and lives in Loveland with her own adopted American Vietnamese kids and her husband, who also works for Hewlett-Packard. Between the two of them, they spend over seventy thousand dollars of their personal income from Hewlett-Packard to support the work of Children of Peace in Vietnam. Binh confided in me that all of her salary goes to pay the costs of the orphanages, and she and her husband even pay out of their own pockets the salaries of the staff at the local Vietnamese government pediatric hospital.

Binh shared with me about her Children of Peace project in 1996 and asked if Project C.U.R.E. would ever be willing to work with her and her orphanages. In January of this year, she called me from her home in Loveland and asked if I would accompany her and a group of her supporters when they return to Hanoi in April. I agreed. We immediately began making the plans for the trip.

My welcome at Hanoi airport was a warm one. The people there met me with a beautiful bouquet of yellow and red roses. The temperature when I walked off the plane in Vietnam was 104 degrees, and the humidity was very high.

I looked around for a telephone so I could call back to Colorado and let everyone know I had arrived safely. I had promised to keep closer touch with the office and Anna Marie after the bazaar twist of events during my recent trip to Thailand in which the Denver office was notified that I was missing in action.

I couldn’t see a phone anywhere, so I opted to wait to make my call home until I got checked into my hotel in Hanoi. However, my hosts threw all my bags into a van, and we headed not to Hanoi but north and west for another forty miles to the city of Viet Tri, the capital of Phu Tho Province. Viet Tri is located in the mountainous areas north of Hanoi and serves as the provincial center for about 1.5 million people. But when I got checked into the hotel, I discovered that the one thing they don’t have in the city is a reliable telephone system. It could take days to get ahold of an international operator who can connect me to Colorado. That part of North Vietnam reminds me a whole lot of North Korea.

Thang Nguyen is a young Vietnamese man from Saigon. He is a nephew of Binh’s but was unable to escape Vietnam in 1975. His father spent fourteen years in a Communist prison in solitary confinement for being an enemy of the Communists. There was no light in his small, wet dungeon cell, and when he came out of prison after fourteen years in the dark, he was totally blind. Binh, on a previous trip, had encouraged Thang to complete his college education. During the years following 1975, Thang had grown up on the streets of Saigon totally by himself. All his family escaped or ended up in prison.

Mr. Nguyen Van Vinh is the country representative for Binh Rybacki’s Children of Peace organization in Vietnam. He is very sharp and has done an excellent job as director in the past. Mr. Vinh speaks four or five languages and now has a top government job.

At 8:15 the van arrived to take our entourage to the Children of Peace home for the disabled and orphaned. I would be able to see Binh Rybacki’s work firsthand. Two years ago, the city of Viet Tri had offered to give her an abandoned middle school that had fallen into severe disrepair. The Communist Party of Vietnam told her that if she wanted to take the challenge to clean and repair the property, she could use it for her orphanage. Binh has done wonders!

As we drove in through the green iron gates, 120 jumping, smiling, chattering kids welcomed us. As is the case with orphanages I visit around the world, all the kids wanted to be talked to and touched and held … all at once. And like the kids in the African orphanages, it didn’t take long for them to discover that I am not only a different skin color, but I also grow hair on my arms. Their curiosity inevitably led them to start pulling on the hairs to see if they were attached. But the serious pulling and tugging was on my heart. If you don’t want to be totally spent emotionally, then don’t run the risk of visiting an orphanage in a developing country.

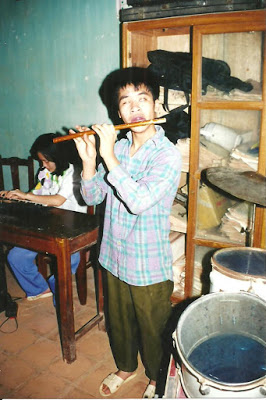

Perhaps the experience that was most wrenching and exhilarating at the same time was watching three young, blind musicians perform for us. Two young boys and a young girl sang and played their hearts out.

The instruments they played included an old, beat-up set of drums with bent cymbals and ripped drum heads; an ancient, one-string, horizontal, guitar-type tube; and a small electronic keyboard donated to the orphanage by some mission group headed back to America.

The one sixteen-year-old boy, De (with the vowel pronounced like “debt” or “death”), also played a bamboo flute. He is good enough, in my opinion, to grace the stage of the Colorado Symphony any day. He also wrote some of the songs he sang for us. Of course, they were in Vietnamese, but Binh interpreted the words into English as he sang.

The words of his first song said, “If I could see my mother—if I had a mother—her hair would be long, and her voice would sound to me like the singing of the birds.” As he continued, it came crashing into my conscious mind like an eighteen-wheeler semitruck bashing its way into a supersilent, sound-controlled recording studio. This boy had never, never, ever known his mother. He was orphaned at birth, and he was blind at birth. He was singing about the mother he had never known, if he even had a mother! His hope was in the idea of a mother and a father! Instead of listening with my ears, I started listening with my heart as he sang his next original song:

I have never seen sunlight

Nor have I seen darkness

All I have known

Is my mother’s sweet voice

And my father’s warm embrace

Mother guides me with her gentle heart

And Father lends me his strong hands on my shoulders

I may never see sunlight

Nor will I know darkness, for …

My mother is my sunlight

And Father will guide me

Through darkness.[1]

By the time De finished, Binh was crying and I was crying. God may not have given De sight, but he withheld absolutely nothing from De from the great storehouse of insight.

1 Written by Nguyen Van De, 1995, Viet Tri Center for Handicapped Children and Orphans. Used by permission

Nest Week: Miracle of the Water Deal

© Dr. James W. Jackson

Permissions granted by Winston-Crown Publishing House