Afghanistan: August 4, 2002: We drove out from Mazar-e Sharif to an area called Balkh. It was the home of about 150 refugee families. They were IDPs, as opposed to being refugees from another country seeking safety in Afghanistan. They were a part of a larger segment of the community but had not integrated into the rest of the community.

Their living quarters were within the walls of bombed-out buildings two and three stories high. The buildings had been completely gutted by the explosions and fire. The new inhabitants pitched their tents on the dirt floors of the old structures and any earthly belongings they retained were stashed under the makeshift tents. There was no running water available to them and no sewer facilities. They had no means of income and were relegated to beggar status.

Our bus pulled up in front of a high-walled enclave heavily guarded by plain-clothed and uniformed soldiers. All were carrying automatic weapons or shoulder-held grenade or rocket launchers. Daniel asked me to accompany him into the fortified enclave.

The walled enclave was heavily shaded by large trees and there were remnants of a couple of large concrete and stone pads at the center. At one time in history the location must have been quite lovely. Along one outside wall there were about 15 Afghanistan tribal men seated in an oval configuration on dark red Persian carpets that had been spread on the ground. All were grizzled and seasoned older men with full beards, traditional parahan turbans, and Afghan turbans. We had gone to the very headquarters of the warlords for the northern part of Afghanistan.

Daniel Kim had always made it a practice to pay a call to the area warlord, Commander Chief Miramza, to greet him, inform him of why he was in the area, and ask his permission to hold the free medical clinic and distribute the bread and fruit to the refugees.

The warlord was a robust man dressed in military fatigues and wearing an unusual bit of headgear. Instead of the traditional turban he wore a round ring over his baldhead with a flat piece of material over the top. But looks aside, the order for the moment was definitely dignity and respect.

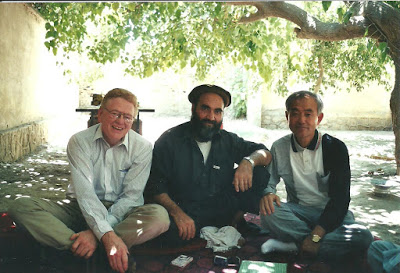

We greeted Commander Miramza by formally embracing and shaking hands. We were then invited to sit in the formation next to the warlord on the bright red Persian rugs. We explained what our agenda was for the day and then Daniel Kim explained all about Project C.U.R.E. and introduced me to say some words of greeting to the council.

From the leaders’ enclave we drove to the refugee area. Some of the people were living in brush arbors made of sticks and weeds piled over a framework to shield the families from the extremely hot sun. The temperature was about 106 degrees even at that early hour. I watched but simply could not understand how even the refugee women could tolerate wearing the long covering over all their other clothes, over their heads and faces. Even inside their brush arbor tent houses they still kept their heads covered although some had removed their chadiri in their makeshift houses.

As we walked into the refugee area the tribe leaders led us to a mound of dirt elevated about five feet above the regular landscape. The top of the mound was flat and measured about 20 feet in diameter. While we were standing there men came with shovels and hoes and knocked down all the large weeds that had grown over the mound. When cleared they brought pieces of carpet and spread on the flat surface.

We unloaded 5,000 loaves of Afghan bread from two vans and stacked them on the pieces of carpet. Daniel Kim and Young Nak Foundation had pre-arranged for the bread ahead of time and had paid for men to collect the loaves from various local bread makers right at their outside ovens.

When the bread was unloaded we set to work unloading 150 large melons and stacked them on the edges of the carpet in front of the bread. Our next duty was to count out exactly 30 loaves of bread and put them in 150 individual stacks.

While we were working with the bread and melons, the Korean medical team of three doctors plus nurses, assistants, and interpreters, set up a clinic site on the porch of an old, bombed-out building. Each individual or mother of sick children was issued a piece of paper with a sequential number on it. That piece of paper allocated a place in line for those wanting to see a doctor.

At the beginning, the refugees kept pretty orderly in the lines. But as time went on the would-be patients began to get restless and some of the more aggressive women tried to push and shove their way closer to the front of the line, or they tried to go around the house and sneak onto the porch from another direction.

As I observed, I came to the conclusion that the Afghan culture was quite a ruthless and physically cruel society. Delegated or self-appointed men of the tribe began to enforce the crowd’s behavior. They were equipped with thick green branches. At any perceived misbehavior of the “rule breakers” in the lines, the men with the sticks would violently attack them and beat them severely until they either ran off or complied.

As I watched it seemed to me that, indeed, the cruelty of the men toward the women was made easier since they really didn’t have to reckon with the identity or personality of the women they were beating. But identity of the misbehaving children didn’t seem to affect the striking of the kids in any way. They just got a beating.

As the sun bore down and the time drug on, there was more violence. Women pushed and shoved other women and there was a lot of abuse from the women to the children. Under pressure, it seemed like the only way to communicate was by hitting.

By 3 in the afternoon, the refugees were getting restless. I told Jason to watch how the crowd was reacting. I pointed out just how nasty crowds like that could become in a split second. I even told him of our experience in Baku, Azerbaijan, on the Caspian Sea when Project C.U.R.E. had teamed up with Dr. Howard Harper and Vision International to perform free inner-ocular lens transplants on blind children. When the time had come for us to shut down the procedures and leave, those parents and grandparents of children who had not received the sight-restoring operation became very emotional. They had anticipated that their children would see again like the other eighty-some blind children who had received their sight as a result of the procedure. “You can only imagine how it would feel to come so close to having your deepest need met and then realize that the people who could help others were leaving without helping you.”

I went on to explain that it probably was one of Anna Marie’s most emotional times of her life, when as we were getting ready to leave, the parents and old people would go to her and beg and even offer wads of money if our doctors would stay and also make their babies see again. “It’s a real thin edge of emotions when a crowd of people realize that they might get left out. It can turn violent very easily.”

Daniel Kim sensed what was happening and spread the word that we would shut down the free clinic at 3:30 p.m. The people also sensed what was going to happen.

Suddenly men started pushing past the nurses and just grabbing bottles and sacks of pills. One man I saw was running away with about six bags of intravenous fluid. Those IV fluids would do him absolutely no good at the present or in the future but he wasn’t going to be denied his share.

When things started to unravel, we packed and closed up the boxes of medical supplies. We each carried what we could and quickly headed for the bus.

Meanwhile, Jason and others were distributing the loaves of bread and melons to the refugee families. The head of that refugee community was standing atop the mound and calling out the individual family names of the camp. When their name was called they would go up on top the mound and receive their 30 loaves of bread and their fruit. But, some folks were greedy and not willing to settle for order. Earlier their family had possibly already received their food, but they wanted more.

Before all the bread could be distributed fairly some of the men in their 20s or 30s began breaking through the lines and grabbing the bread and running off. Then the rest saw what was happening and rushed the mound.

At that point Daniel Kim hollered to Jason and the others handing out the bread and fruit and told them to just drop whatever they had in their hands and quickly go to the bus. By that time the young men were trying to grab anything they could get their hands on. They began trying to strip the waist pack Jason had fastened around his middle. They could not get it unlatched or the pockets unzipped. But someone did reach in and grab a hold of his camera from one of his side pockets. He ran back and grabbed it back from the young man and quickly made his way to the bus.

Now then, at a church picnic or even at Denver’s National Western Stock Show, such an incident wouldn’t be too significant. But, when nearly every man in the community was carrying an automatic high-powered rifle or a grenade launcher and you are a citizen of a country that just recently bombed the “puddin’” out of the neighborhood, you are apt to have the makings of something nasty or at least dangerous. I was very pleased when Jason and I and the 18 Koreans were safely seated on the bus.

Jason was a little shaken from the incident. It was the first such occurrence he had ever witnessed. In fact, our trip to Uzbekistan and Afghanistan was the first time Jason had ever been outside the US.

Next Week: “We’re on Fire”

© Dr. James W. Jackson

Permissions granted by Winston-Crown Publishing House