In March of 1999, the U.S. State Department closed our Embassy in Belgrade and withdrew all diplomatic support personnel. Travel restrictions and travel warnings had been issued. Secretary Albright and NATO had made the threat of air strikes, and without the signatures on the proposed accord, bombing by U.S. aircraft began on March 24, 1999, and continued through June 10, 1999. During those seventy-eight days of continual air strikes over the Serbian Republic of Yugoslavia, 25,200 sorties, or missions, had been flown in which 1,100 aircraft took part dropping more than 25,500 tons of explosives on the Serbian territory of Yugoslavia. The total force of the destructive explosives was more than ten times greater than the force of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. All of that action was without ever having declared war on a sovereign country, or the U.S. Congress giving any approval of the action. It was strictly a decision by the Clinton Administration.

A huge wave of anti-NATO, and especially anti-American, feeling swept over Yugoslavia and the neighboring countries. It was into that setting that Project C.U.R.E. was requested to go. I had been asked to travel directly into the smoking ruins of Belgrade itself and assess the situation with the idea of supplying medical goods to hospitals and clinics which had, because of the extent of the conflict, depleted their resources.

The U.S. State Department, along with the International War Crimes Tribunal, announced they were placing a five million dollar price tag on the head of Slobodan Milosevic. Serbia restricted its borders to keep out bounty hunters. I was finally able to secure a visa for my passport through Yugoslavia’s Embassy in Canada.

Once I had checked into my room at the Moskva Hotel in downtown Belgrade, I realized there was no air conditioning. When I opened my hotel window I additionally realized I was right in the middle of a huge political protest rally. The protesters were demanding the ouster of President Slobodan Milosevic. They were also registering their extreme disfavor of the U.S. and NATO military actions. I was in the middle of some intense emotions.

From the relative safety of my hotel room, I curiously studied the activities of the individuals gathered in the large intersection below. As a Cultural Economist, I was seeing more going on in the intersection below than just frustrated and angry protesters. I was seeing the clash of economics and culture taking place in its rawest form.

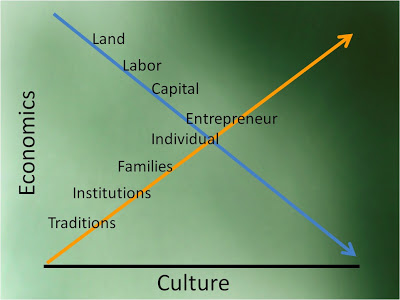

The study of economics has to do with the efficient allocation and organization of resources for production. Cultural economics concerns itself with the relationship of culture to economic outcomes. A given culture will influence political systems, traditions, and religious beliefs, the positions of importance held by the families, the formation of institutions, and the value placed on individuals. Likewise, economic systems have the power to affect and shape the cultures. All of those factors were in play in the intersection below.

My past thirty-five years of international travel have greatly influenced my beliefs and world view. I have had the opportunity of standing in Moscow, Russia, and personally witnessing the collapse of the old Soviet Union. I was in Brazil and Argentina when their unraveled economies were experiencing three thousand percent inflation. I was in Zimbabwe while they experienced the consequences of the foolish mistakes of the Robert Mugabe regime. I have been in Iraq, Afghanistan, Cambodia, and China while they were going through their cultural upheavals. I have come to believe that global transformation, national transformation, corporate transformation, and individual transformation has everything to do with cultural economics.

Culture, with its components of traditions, institutions, families, and individuals, intersects with classic economic factors like land, labor, capital, and the entrepreneur. It is there that history takes place. It is at that intersection of culture and economics that transformation occurs.

But how does culture influence and dictate economics as it travels through that intersection? How do economic factors influence and dictate culture as they pass through that intersection?

Whether we like it or not, we each have a curbside involvement in that intersection, and I find that exciting and fascinating. Everyone alive has gathered at the curbside of the intersection of culture and economics.

Each person has been busily shopping at the market place and carries a fine market basket in his or her hand. Inside the market baskets are the most valuable possessions each person owns. The individuals have literally traded their lives for what they have in their baskets.

The personal inventories in the baskets include financial possessions and individual possessions of physical, intellectual, emotional, volitional, and temporal characteristics. Family, friends, and influence are included in the relational possessions. Also included are spiritual and other special possessions that are unique to each individual.

All of the shoppers are gathered there at the curbside of the intersection of culture and economics with their market baskets in hand. They possess the power and opportunity to ultimately determine what happens at the intersection of culture and economics. They hold history in their hands: by injecting the things from their market basket into the traffic flow of the intersection, they determine the direction, timing, and outcome of the flow of traffic.

The greatest and most powerful question that faces each one of us gathered at that intersection, regarding the contents of our market baskets is, “What’cha Gonna Do with What’cha Got?” How we answer that question determines the outcome and recordation of history.

What is it that you have in your market basket today? What do you plan to do with it?

After spending considerable time in examining and reviewing what I have in my market basket, I’ve made up my mind and this is what I plan to do: I want to spend the best of my life for the rest of my life helping other people be better off. I look into my basket and see the potential of a lot of evil in this world. But I also see an overwhelming amount of virtue there to be dispensed. I believe that virtue is extremely powerful in its influence.

While standing at the intersection of culture and economics, I would like to be among those who believe that by living and dispensing unrestrained amounts of virtue into the equation of culture and economics, we can be extremely effective and positive agents of cultural and economic transformation.

Someone once told me, because things are the way they are, things will not stay the way they are. Or, as C. S. Lewis would say, “It may be hard for an egg to turn into a bird: it would be a jolly sight harder for it to learn to fly while remaining an egg. We are like eggs at present. And you cannot go on indefinitely being just an ordinary, decent egg. We must be hatched or go bad.”

I don’t want to rot or go bad. I do want to hatch and become a dynamic transformation agent bringing help and hope to the people in my world.