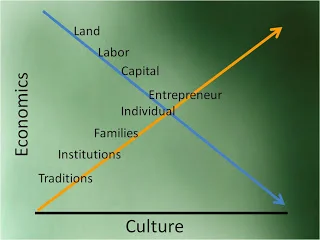

If you eat, you are a part of America’s agribusiness. I have chosen to use the agribusiness system to demonstrate our often discussed maxim that transformation takes place at the intersection of culture and economics. It is also my intention to share here, just as an example, how our government’s political habit of intervention into our systems invades and destructively interferes with our basic economic principle of free enterprise.

Along the way, we may even discover that the further we wander from the simplicity of the market forces, the further we move away from effective and responsible allocation of our economic resources. Marx never got it right, and FDR couldn’t get it right. A centralized governmental economic system of redistribution, quite simply, has never been successful.

Our government has subsidized agriculture since the 1930s with farm policies that include: (1) propped up farm prices, and subsidized incomes, (2) agriculture-related research, (3) farm credit, (4) water and soil programs, (5) crop insurance, and (6) giant subsidies on the sales of farm products into world markets.

Roosevelt’s Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 was predicated on the assumption of the parity concept: if a farmer could take a bushel of corn to town in 1912 and sell it for enough money to buy a shirt, he should be able to sell a bushel of corn on any day and buy the shirt. The security of that logic really appealed to the farm families. They would vote for FDR forever. The relationship between the prices received by farmers for their output and the prices they must pay for goods and services would always remain the same. If the price of shirts tripled over time, then their price of corn would be guaranteed to triple also.

That bought Roosevelt the votes, but it didn’t buy him a Nobel Prize in economics or logic. Economists through the years have uniformly rejected the parity notion. There is no sound reasoning in the proposition that if a bushel of corn could buy a shirt in 1912, it should still be able to buy a shirt several decades later. The relative value of goods and services is established by supply and demand. When technology changes, or new resources or products come to the market, or styles or tastes change, those relative values also change over time.

In the 1980s you could buy a modestly-equipped, new automobile for the same amount of money that it would take you to purchase a well- equipped computer. But a decade later everything had changed. Certainly, neither the computer company nor the car company would vote for the parity concept.

It did, however, require the government to arbitrarily set price floors on farm products. Those minimum prices were called price supports. Just like Russia’s Gosplan, that approach failed miserably. So, our government simply established above-equilibrium price supports for farm products. That means that the government just ignored what the real world would pay for the products and went ahead with paying the farmers the hyper price. Oops. That really didn’t work.

The farmers dug in and began producing in excess because the government guaranteed that they would get paid for all they could produce at the ballooned prices. They now had money the government had paid them to place more of their land into production, excavate their land so that it would produce larger yields, buy fertilizer and better seed. Meat growers, milk producers, and poultry farmers could improve their operations so they could all produce more.

Huge surpluses were created. In the real world of economics when there are surpluses of a product the prices fall, consumers purchase the excess production at a reduced price, and the market quickly levels out. But, the government was obligated to pay the farmers not only the above-equilibrium price, but had to pay for transportation to move the crops around. They also had to pay for storage of the surplus . . . and there were more and more excessive harvests coming on!

The government was then forced to go to the public and raise taxes to cover their own ignorance. The government’s administrative costs exploded as they endeavored to manipulate the programs. The farmers formed lobby groups to protect the good thing they had going. The marginal costs of the extra production far exceeded the marginal benefit to anyone in the society because the product price to the consumer could not be lowered even though there was surplus going to waste.

Since the product price could not be lowered, the U.S. consumers were paying a premium. That made our agricultural markets very attractive to foreign producers, who enjoyed getting in on the premium amounts being paid. The U.S. then had to quickly impose import barriers, tariffs, and trade quotas.

So the Roosevelt Gosplan came up with a brilliant idea. They could save millions of dollars of administration, transportation, storage, and other program-support costs if the farmers would simply stop growing so many crops. But it was impossible to simply stop the whole craziness and let the free enterprise system straighten out the mess. They could not run the risk of making the farmers angry and lose a full twenty-five percent of the national vote. So, they decided to pay the farmers to not grow the crops, and the payments would be based on what they had been growing the past year. Oops.

In return for guaranteed prices for their crops, the farmers had to agree to limit the number of acres they planted in that certain crop. That was referred to as acreage allotments.

(I’m terribly sorry, but I must share with you the picture I am seeing in my mind. I am chortling to myself as I write this piece. We are so critical of Marx, Lenin, and Joseph Stalin and their Gosplan, but in this scene all the same people are sitting around all the same tables, with their heads all pointed into the group. They don’t have computers or calculators so there are reams of paper on the floors and on the tables as they try to figure out the Gosplan formula by using long division and multiplication with short, stubby pencils. The difference is that some are dressed in green Russian military uniforms and some are in ties, nice dresses and suits. Some are in Moscow, and some are in Washington, DC. All have a disdain for cultural and economic free choice, all are obsessed with the craze to totally control the economy, and all are running madly away from the concept of free enterprise.)

The policy designers of the U.S. Department of Agriculture had to estimate the amount of product the consumers would buy at the supported price. They then had to translate that amount into the total number of acres the farmers would have to plant to provide that farm product. The total acreage then had to be apportioned among states, counties, and down to the individual farmers. Oops! They could never make it come out right, because all their planning did not reduce the surpluses. The acreage reduction did not result in proportionate decline in production. Some farmers would include their worst land in the allotment and save out their best land to continue to grow their crops. Now they had even more money to purchase better seed, take advantage of pesticides and enriched fertilizers, and buy the newest farm equipment. All of that increased and enhanced their output per acre. It did not shrink the surpluses. Additionally, farmers who did not go along with the subsidies stayed out of the program and bought up more acreage and planted more in anticipation of the artificially increased overall prices that would be paid. The surpluses continued to grow.

Oh, what’s to be done? What’s to be done? The surpluses continued to build and the payments used to not grow crops kept increasing. Octave Broussard and his friend Bordeau continued to make money for not raising hogs and money for not growing corn that was not fed to the hogs that they were not raising!

Governments that ignore basic economic principles like supply and demand; scarcity, choice and cost; and the efficiency of the free market, in order to manipulate a nation’s culture for their own greed, have a difficult time making the intended results all come out right. Eventually, those governments step on the neck of the goose that has been laying the golden eggs of the economy.

Next Week: Well, Try Messing with the Demand

(Research ideas from Dr. Jackson's new writing project on Cultural Economics)

© Dr. James W. Jackson

Permissions granted by Winston-Crown Publishing House