While traveling and working in most of the countries of the world, I am continually amazed by the fact that most of the people living within those particular countries understand very little about how their political and economic systems work, or why they, the citizens, are expected to perform and behave in certain ways. They just do it!

In North Korea or Cuba, the people simply get up, put on a shirt, and climb into the back of a waiting truck and are hauled off to tend rice paddies or fields of pineapples. In Taiwan, it is necessary for the people to find their own way to work in order to sit all day long next to a conveyor belt and assemble very small parts for very big television sets. In America, a lot of people don’t even go to work at all. Why is that?

It all has to do with the economic and political systems that have been chosen and implemented in the different countries. As my graduate school major economics professor, Dr. Paul Ballantyne, used to insist, “It is abundantly clear that economic and political systems matter!”

National polls indicate that most American students neither understand how a market economy functions, nor grasp the most fundamental concepts underlying all economic systems(1) Perhaps the most influential economic work of the 18th century was a book entitled An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, a book written by the Scottish economist Adam Smith (1723-90), explaining the principles of capitalism and free enterprise. He believed that governments should not interfere with economic competition and free trade, which is necessary for strong economic growth.

Adam Smith used to say, “Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice: all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things." Adam Smith had a tremendous influence on the Revolutionary fathers of young America.

One hundred years later, German philosopher Karl Marx (1818-83) wrote perhaps the most influential economic work of the 19th century, Das Kapital. He disagreed with Adam Smith and wrote his work to explain the principles of collective communism. He argued that the only solution to the class struggle between worker and employer was for the government to own everything and totally control distribution. Marx believed “the class struggle necessarily leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat.” He also declared that the redistribution must be determined by an elite few, called the politburo, and they would make their decisions based on the idea, “from each according to his abilities, and to each according to his needs.” Socialism automatically becomes a by-product of this system.

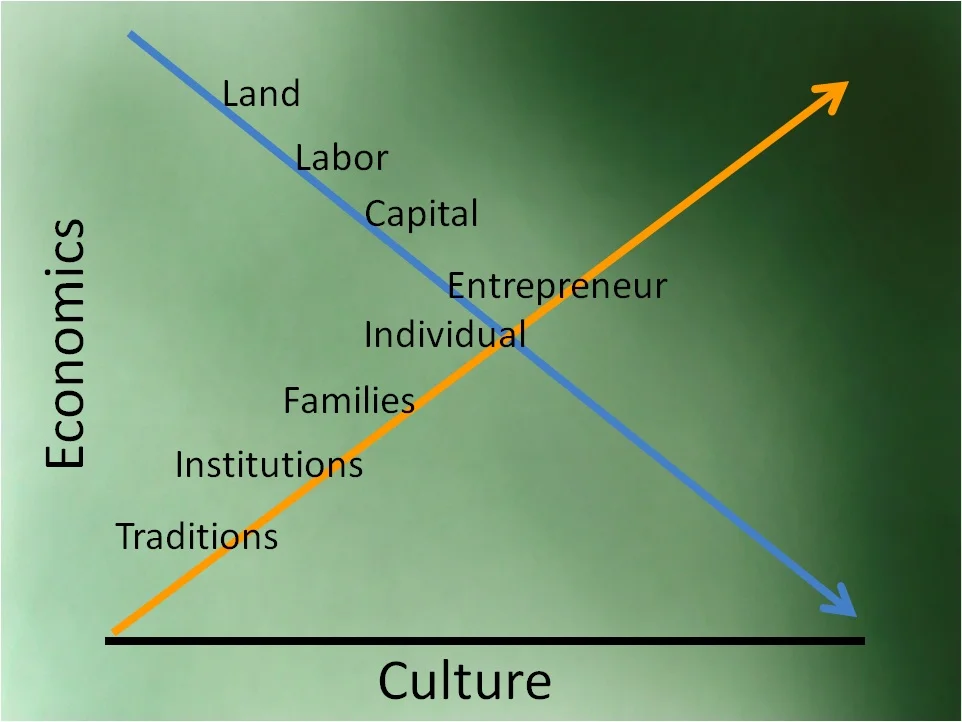

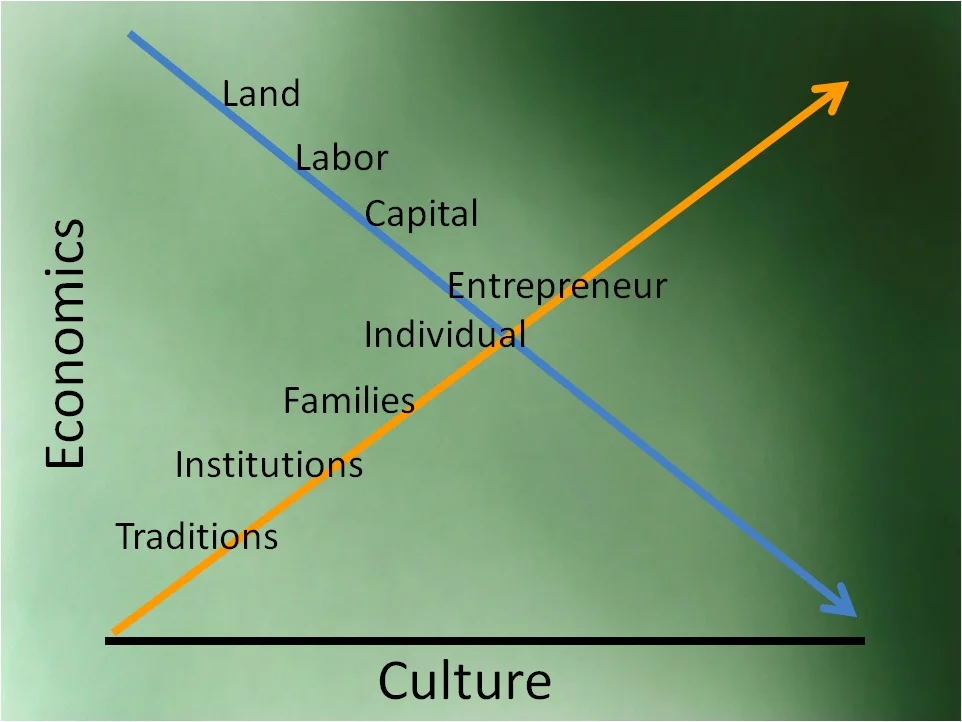

Without being too simplistic at this point, let it be stated that all economic/political experiments being carried out by nations today are divided at the point of

Income Growth vs. Income Redistribution.

The tensions between those two camps of economic systems are the fundamental reasons for the political experiments of the past 200 years. Free enterprise economies as seen at work in the United States and Canada have been primarily concerned with economic growth and expansion with a heavy emphasis on the freedoms of the individual.

The early communists believed that poverty, income inequity, and interpersonal oppression came because of free enterprise economies. In an endeavor to save the world they outlawed all market forces. As a result, some notable consequences can still be sited in places like the old Soviet Union and North Korea: millions of people starved, valuable resources were wasted and the economies damaged, sectarian violence quelled by brute force, basic lifestyles reduced to meager existence. And when the voluntary incentive to participate in the grand social experiment begins to fade away, pogroms of punishment and genocide have been relied upon to continue the desired political or economic results.

It will be well worth our time to discover and review for our own knowledge and security some fundamentals of the idea of free enterprise, the elements of free enterprise, the effectiveness of free enterprise, and perhaps even look at some alternatives to free enterprise.

Next Week: Systems Matter Part 2

(Research ideas from Dr. Jackson’s new writing project on Cultural Economics)

Permissions granted by Winston-Crown Publishing House